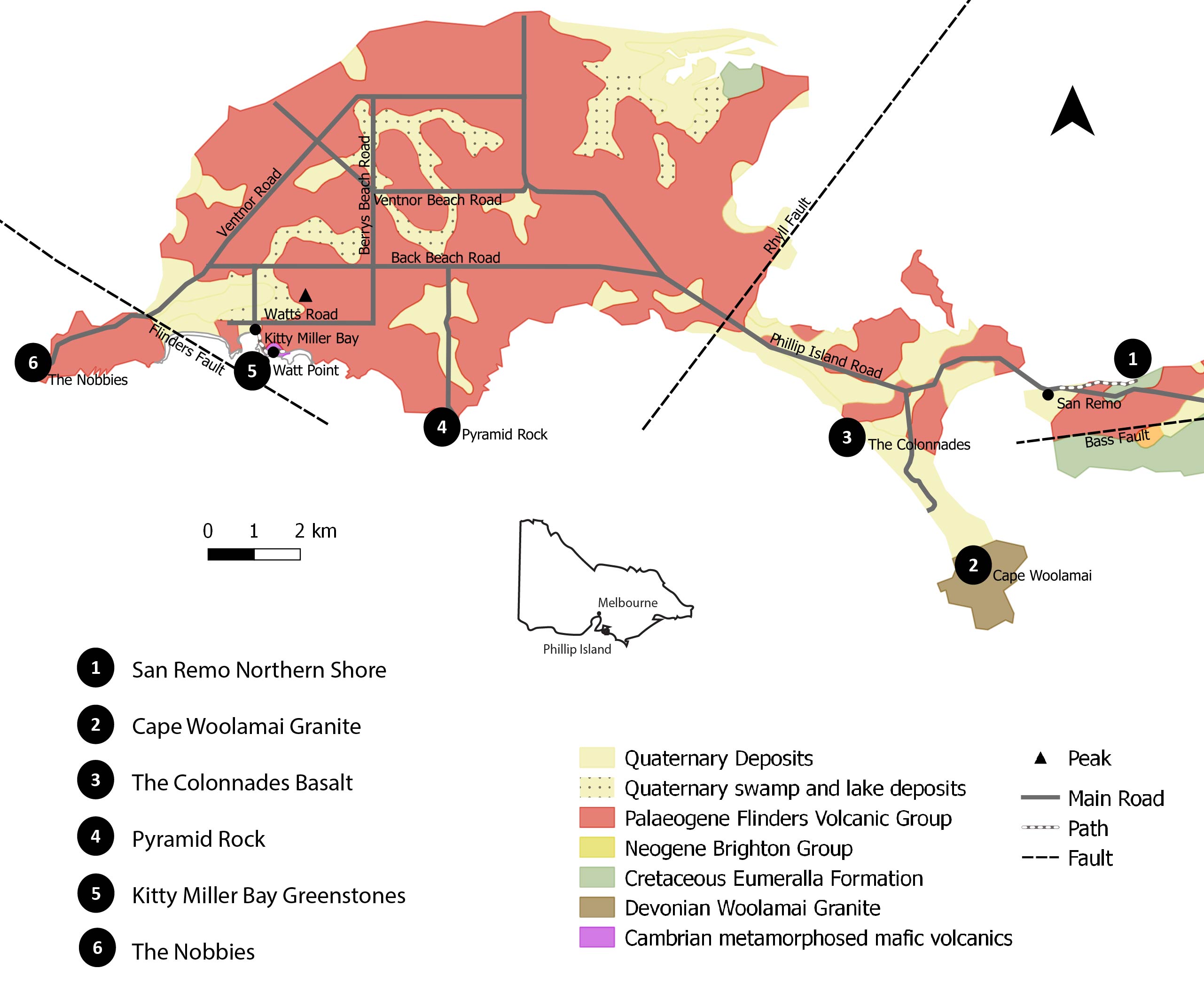

Phillip Island is located in Western Port, approximately 120 km south-east of Melbourne. The island is rich in history, both human and natural – over 500 million years of it! Nature is a huge draw point, with over 3.5 million tourists a year flocking to the island to experience the iconic rocky coastal landscapes, as well as spot a cheeky penguin at Penguin Parade or, view up to 30,000 seals at Seal Rocks (Point 6 in Figure 1).

The Geology of the island is dominated by numerous basalt flows, collectively called Flinders Volcanic Group (Figure 1, Stops 3, 4 and 6). At San Remo (Figure 1, Stop 1) you can see in the coastal cliffs the contact where the basalt flowed over much older Cretaceous Rocks of the Eumeralla Formation – the same rocks which outcrop at Cape Otway. Cape Woolamai in the island’s south-east has a distinctly different character, with coastal outcrops dominated by the rounded Cape Woolamai Devonian granite intrusion (Figure 1, Stop 2). At Kitty Miller Bay (Figure 1, Stop 5) however, the rocks reveal a much more ancient history and a long-lost connection to Tasmania.

The history of the island begins in the Cambrian – around 500 million years ago. This was a period of time globally where there was an explosion of complex multi-cellular life forms in the ocean. The land surface was still barren and Victoria as we know it had not yet formed. The position of Phillip Island was, at this time, most likely deep under the ocean looking something similar to the video below.

There are three North-South trending belts of Cambrian rocks in Victoria (Figure 2). As you can see, however, the greenstones on Phillip Island do not line up with any of them! Some researchers think it’s an entirely different belt, others think it’s been shifted left or right by faulting and there’s even a few who have postulated that these greenstones are actually related to outcrops in western Tasmania!

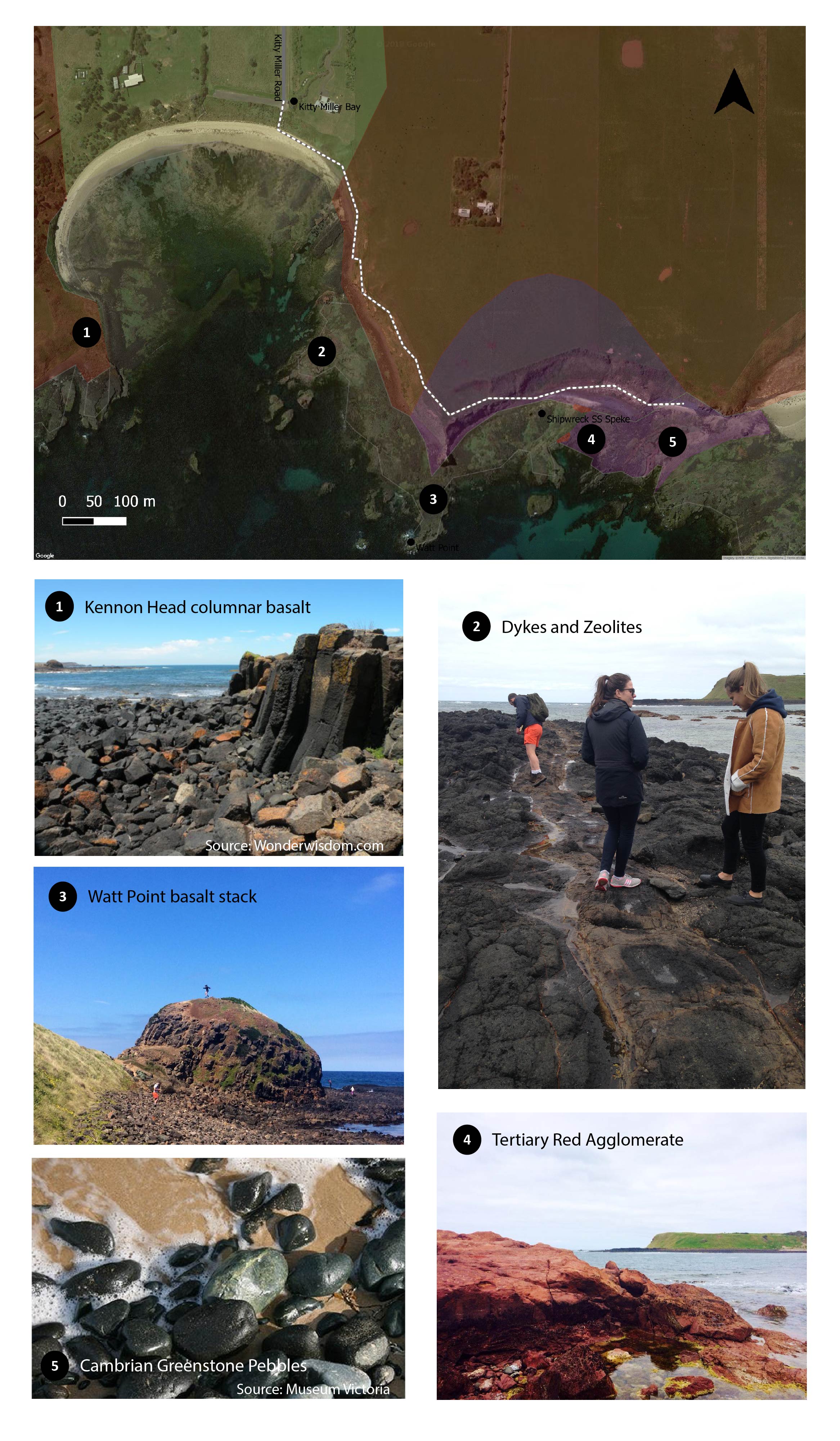

The Cambrian Greenstones are overlain uncomformably by extensive Tertiary (Paleogene) lava flows. An unconformity develops when there is a time gap between two layers lying on top of one another (i.e. due to erosion). Columnar basalt can be viewed along the western arm of Kitty Miller Bay (Kannon Head, Stop 1 in Figure 3). The formation of columnar basalt is explained in the Field Trip for Organ Pipes.

As you make your way to Watt Point stumbling over basalt boulders, look carefully at the gravels and basalt outcrops for agate, chalcedony and zeolites. Along this shore platform there are also a couple of distinctive linear features cutting through the basalt (Figure 3, Stop 2). These are dykes, which form when magma shoots upwards through cracks in the rock layers.

Passing by (or climbing) Watt Point – an impressive stack of basalt – you come to a view of the remains of the S. S. Speke, which crashed into the rocks at Watt Point in 1906. Continuing past the wreck (after a quick photo!), you may notice large outcrops of bright orange-red sediments and rocks of volcanic origin (Tertiary Agglomerate). This is most likely due to Iron-rich clays forming from the weathering of volcanic rocks (high iron content). The greenstones are stained red on this contact.

Also scattered along the beach here are green pebbles, sourced from rigid outcrops of Cambrian Greenstones at Stop 5 (Figure 3) as well as further out to sea below the low-tide mark. The rocks are green because of the minerals they contain, including chlorite, which form through metamorphism (cooking) of the host rock at great pressures deep in the Earth.

Cape Woolamai is a giant granite outcrop (Figure 1, Stop 2) and so is distinct from all other areas on Phillip Island. It can be explored through walking the Cape Woolamai Coastal Walk. The granites in Victoria are dated back to the Devonian (or around 360 million years ago). This means that it is older than the basalt, intruding the Cambrian basement at depth. Intruding here means hot magma rising up from deep in the earth to settle and crystallise over many years.

It was only after millions of years of weathering and uplift that it was exposed at surface again for us to explore and wonder at in awe (Figure 4). Looking closely at the granite you’ll notice it is pink in colour and course-grained with mostly quartz and oligoclase (feldspar that weathers to pink!) crystals.

The Colonnades, Pyramid Rock and The Nobbies (Stop 3, 4 and 6 in Figure 1) are all fantastic exposures of basalt flows. The only known location of an actual eruption point on Phillip Island is Quoin Hill, which operates as a quarry just north of Watt Road.

If we pay particular attention to the site at Pyramid Rock (Figure 5), a few clues are revealed that tie the formation of the landscape together (source). The pinkish rocks at the base of Pyramid Rock are actually Woolamai Granite.

Climbing on over to the mound in the foreground, you’ll notice some very hard weathered sediments forming sharp (literally – watch your hands) scarps (Figure 6).

This gives us a theory for a palaeo-environment in the Tertiary where granite islands in a shallow sea are partially covered by extensive flows of basaltic lava, which in turn were covered by sediments which formed from weathering granite!

We acknowledge the Boon Wurrung and Bunurong as the Traditional Owners of the land upon which this field guide has been created. We recognise that many areas hold deep cultural significance for local Aboriginal groups and I hope you will keep this in mind as you explore the island.

Excellent website ! Great work …… I assume that you work with Sarah Stark

LikeLike

Wow, thank you. This was very helpful!!

LikeLike