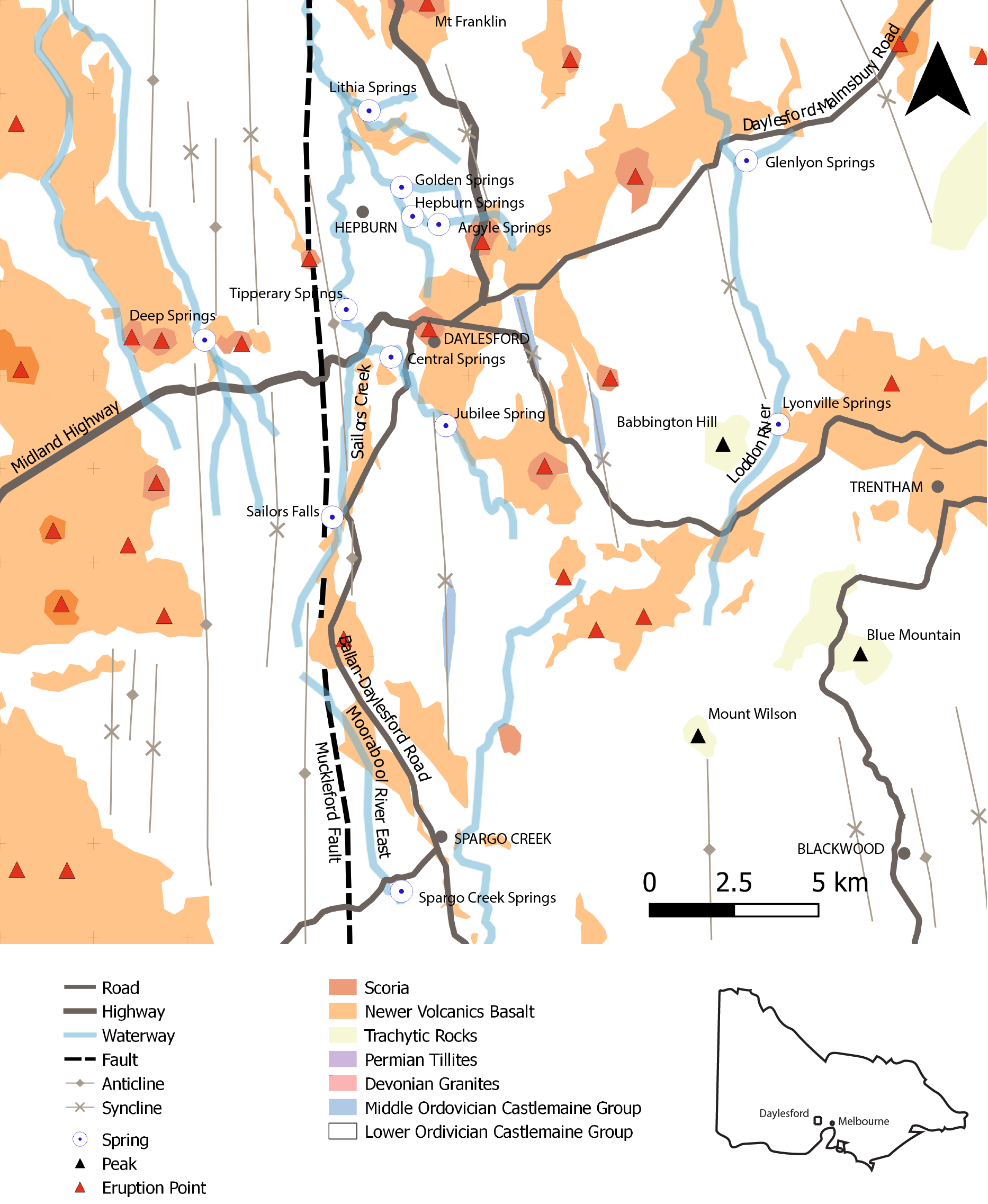

The town of Daylesford is located in the Goldfield’s Region of Victoria, a 1.5 hour drive from Melbourne CBD. It is a place of indulgence and relaxation, chocolates, bookstores, scenic trails and very cool geology! The main attraction to the area, however, are the natural mineral springs which are dotted around the Daylesford area (see map below). There are a number of walking trails, including the Tipperary Track, which will take you through the lesser known springs.

The region is located in the Victorian highlands,700-800 m above sea level, to the west of the Great Dividing Range. The stratigraphy of the area consists of three groups: the Ordovician Castlemaine Group basement sedimentary sequence, intruded by late-Devonian plutons and overlain by cover-sequences including Permian Tillites, Newer Volcanics Basalt and Quaternary sediments.

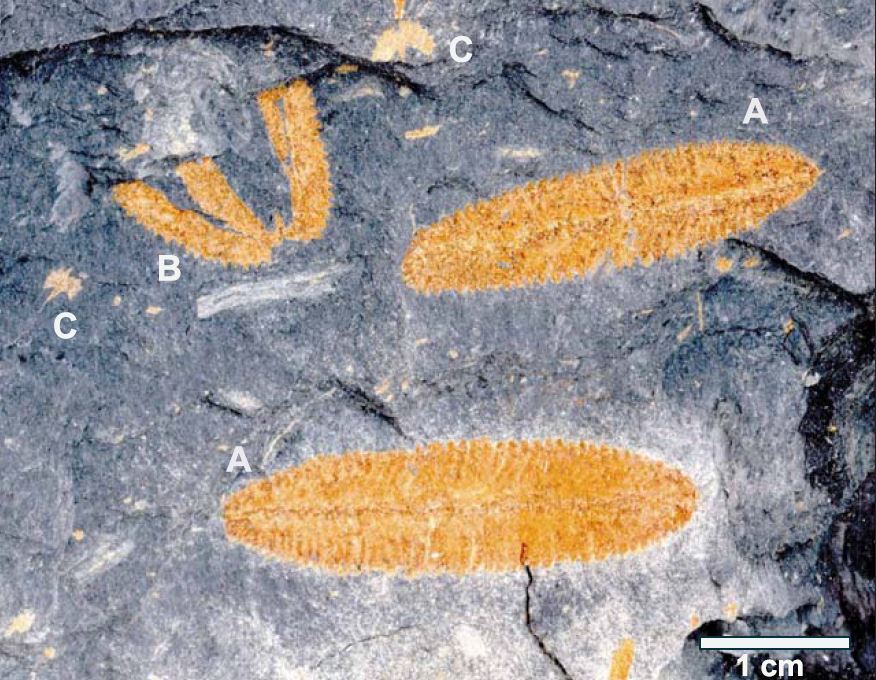

The Castlemaine Group outcrops extensively in the region. The sequences vary from mudstone-dominant to sandstone-dominant with complete Bouma Sequences (Turbidites; see: Maria Island for an explanation). Biostratigraphic methods are used to subdivide the group into lithostratigraphic units, a.k.a. fossils. Graptolites can have very narrow age ranges and so scientists can ascribe specific graptolite species to specific units. The layers have all been folded and faulted extensively, with a dominant north-south trend (see map above).

The Castlemaine Group is uncomfortably overlain by Newer Volcanics basalt flows. The basalt flows are termed ‘Newer Volcanics’ to differentiate from the ‘Older Volcanics’ Group which was depsited 42-57 million years ago (Ma). The Newer Volcanics correspond to a peak of volcanic activity which began seven million years ago (Ma) and has the potential to continue to the present. Bet you didn’t realise there could still be magma bubbling beneath the surface of Victoria!

There have been over 75 eruption points identified mainly from aerial photographic interpretation – a few of these have been included in the map above! Basalt lava flows are highly viscous (runny), filling valleys and rivers as well as their tributaries. This accounts for their dominant northerly-trend.

Viscous basaltic lavas are not the only type of igneous rock which outcrops in the area. There are also Trachytic lavas and lava domes, including Babblington Hill, Mount Wilson and Blue Mountain in the south-east and Spring Hill in the north-east. There are many differences between these two types of igneous rocks, including silica content, viscosity, mineral composition and mechanism of formation. These are also the oldest known Newer Volcanic Group rocks in the region (~6 Ma). The Mount Franklin Complex interestingly represents some of the youngest volcanism in Victoria.

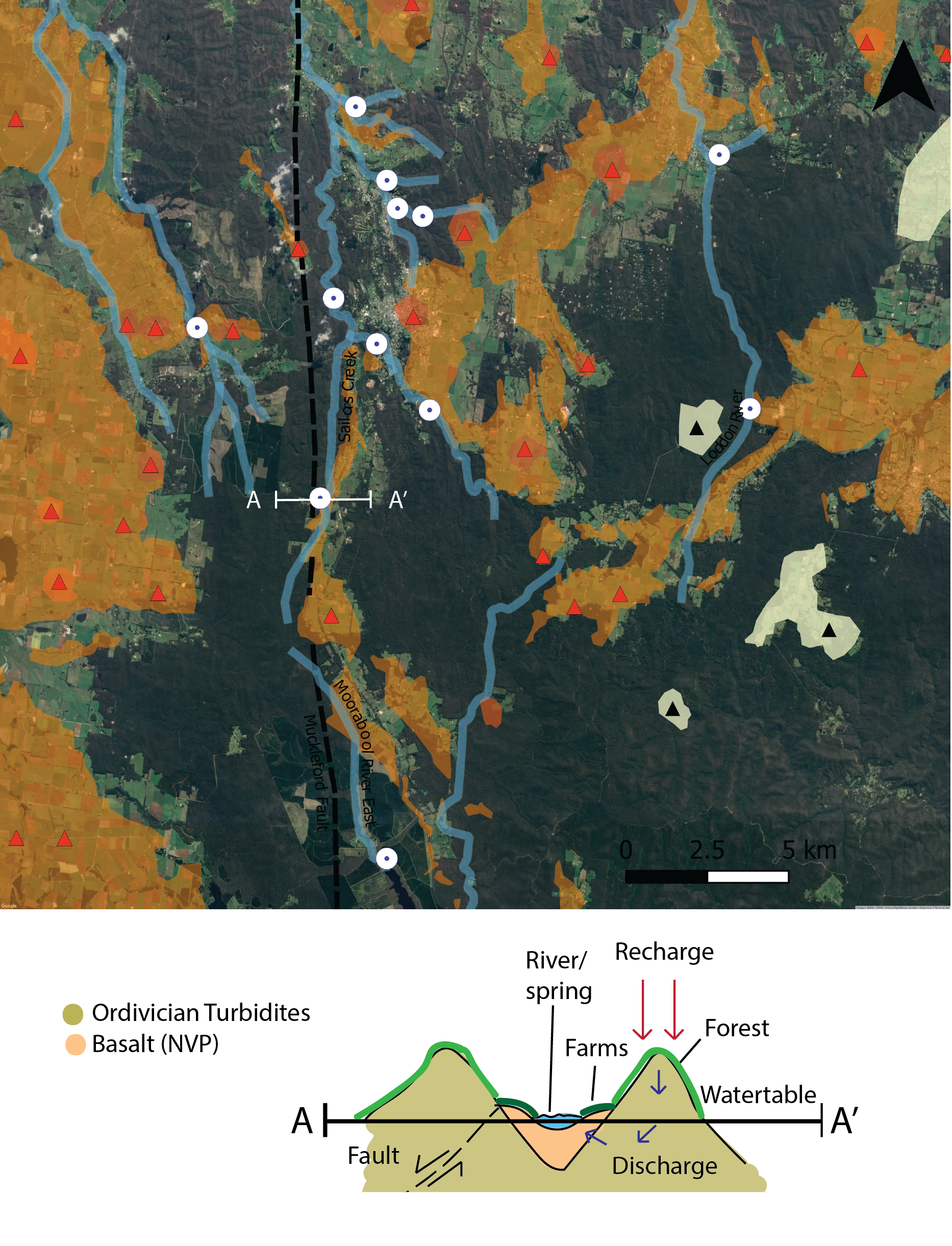

The distribution of the basalt in the landscape has had significant impacts on historical land-use, particularly farming and gold mining. It is clear in the map below that fertile farming land correlates almost exactly with the distribution of basalt flows. The Ordivician turbidite sequences generally form highlands and correlate with scrubby bushland, as well as National and State Parks.

The gold deposits in the area are associated with erosion of quartz-veins within the Ordivician Turbidite sequences into streams and gullies – much like Bendigo. In Daylesford, however, these alluvial gold deposits became covered and ‘protected’ when basaltic lava flows filled the valleys. Miners would dig until they broke through the basalt, roughly sieving the sandstones and shales underneath for their golden prize. People still fossick for gold at Sailors Creek (req. miners right).

The image above also demonstrates the significance of the locations of the springs in low-lands, generally at a contact between the basalts and basement sediments and often in proximity to faults. It is believed the source of the CO2 in the mineral springs is igneous-derived, with ground-water circulating through the igneous rocks.

There is a great deal of variation in the characteristics of the individual springs. You can experiment and discover this for yourself through one of your senses: taste!

At Tipperary Springs the water is highly carbonated and has a slight taste of rust whilst at Hepburn Springs the water is flat and has more of a Sulphur odour. Different minerals are leached into the water depending on the path it takes from deep in the ground to the surface and this affects the taste. Plaques are available to read at each spring, detailing the chemical constituents of the water.

Something you will notice at all of the springs is the presence of colonial photosynthetic algae – all of the orange, brown and green gooey stuff.

Algae is usually green, but here it is orange. Why do you think that is? Pick some up and look what is underneath (fair warning, it’s gooey!). The orange colour protects the algae from the sun (pigments). Underneath this layer is the non-photosynthetic algae, which smell because they use chemicals to make their energy (Iron and Sulfur, for instance).

This is probably my favourite part about the springs – their link to the earliest life forms on Earth. Even the sorts of life forms scientists are searching for on Mars! Living fossils which you can squish in your hands!

We acknowledge the Dja Dja Wurrung Nation as the Traditional Owners of the land upon which this field guide has been created. We recognise that many areas hold deep cultural significance for local Aboriginal groups and I hope you will keep this in mind as you explore the area.

3 Comments Add yours